by Grzegorz

¯abiñski

1.0 Abstract

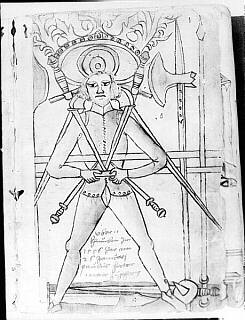

The paper deals with selected aspects of Blossfechten (unarmoured combat) with the longsword as depicted in one of the most renowned, yet still unpublished source of medieval swordsmanship known as Codex Wallerstein (Universitaetsbibliothek Augsburg, I. 6.4°.2). Firstly, the author deals with the very structure of the manuscripts, proving that it actually consists of two different manuals (the one from late fourteenth-early fifteenth century, the other from about mid-fifteenth century, which were later put together). Furthermore, the question of the way in which the section under analysis was accomplished is discussed: it is suggested that the images were put in first, and then provided with relevant comments. Next, the author attempts classifying the weapon presented in the section by means of comparing it to a well-known and commonly accepted typology of Robert E. Oakeshott. Moreover, several remarks concerning the functionality of such particular types of weapon are introduced. Furthermore, the author deals with several general fighting principles as presented in the manuscript, trying to affiliate them to the school of German swordsmaster Johannes Liechtenauer; however, he notices several similarities to other fencing manuals, with special regard to that of Fiore dei Liberi. Then, the comments concerning particular plates and fighting actions presented on them are provided. Next, the author attempts to show several similarities between the actions presented and those depicted in other medieval fencing manuals. Finally, conclusions and suggestions for further research (comprising in the first instance the necessity of a critical edition of the manuscript) are provided.2.0 Introduction

The

aim of this paper is to comment on the unarmoured long sword fighting as

presented in one of the best known late medieval Fechtbuch, the

Codex Wallerstein. The manuscript containing this manual is preserved in

the collection of the Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg (I.6.4?.2). The codex

is a paper quarto manuscript, written in Middle High German, containing

221 pages (108 numbered charts, and several unnumbered ones at the beginning),

numbered every odd one in the upper right corner, starting from page 4

which is given No. 1. Page 1 contains a date 1549, a name of one of the

manual’s owners,[1]Vonn

Baumans, and the word Fechtbuch, while pages 2 and 3 are blank.

This manual seems to consist of two different Fechtbücher (for the

sake of convenience called further A and B), which were put together and

later given a common pagination.[2]

Part A (No. 1 recto—No. 75 recto, and No. 108 verso; thus consisting of

151 pages) is probably from the second half of the fifteenth century, on

account of both the representations of arms and armour on No. 1 verso (full

plate armours and armets) and No. 2 recto, andthe

details of costumes on No. 108 verso.[3]

On the other hand, part B (No. 76 recto—No. 108 recto; 66 pages) is probably

of much earlier origin, which, on account of the details of armour (bascinets

without visors or bascinets with early types of visors; mail hauberks;

garments worn on the cuirasses) can be dated to late fourteenth—early fifteenth

century.[4]

The

aim of this paper is to comment on the unarmoured long sword fighting as

presented in one of the best known late medieval Fechtbuch, the

Codex Wallerstein. The manuscript containing this manual is preserved in

the collection of the Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg (I.6.4?.2). The codex

is a paper quarto manuscript, written in Middle High German, containing

221 pages (108 numbered charts, and several unnumbered ones at the beginning),

numbered every odd one in the upper right corner, starting from page 4

which is given No. 1. Page 1 contains a date 1549, a name of one of the

manual’s owners,[1]Vonn

Baumans, and the word Fechtbuch, while pages 2 and 3 are blank.

This manual seems to consist of two different Fechtbücher (for the

sake of convenience called further A and B), which were put together and

later given a common pagination.[2]

Part A (No. 1 recto—No. 75 recto, and No. 108 verso; thus consisting of

151 pages) is probably from the second half of the fifteenth century, on

account of both the representations of arms and armour on No. 1 verso (full

plate armours and armets) and No. 2 recto, andthe

details of costumes on No. 108 verso.[3]

On the other hand, part B (No. 76 recto—No. 108 recto; 66 pages) is probably

of much earlier origin, which, on account of the details of armour (bascinets

without visors or bascinets with early types of visors; mail hauberks;

garments worn on the cuirasses) can be dated to late fourteenth—early fifteenth

century.[4]

As mentioned, it is difficult to deal extensively with the history of

the codex without having the real manuscript at one’s disposal—anyway,

it is not the purpose of this contribution. However, it is worth noticing

that this Fechtbuch belonged once to one of the most famous sixteenth-century

authors of combat manuals, Paulus Hector Mair;[5]

and it was he who was the author of the contents of the manuscript (No.

109 recto), and several minor remarks on the number of pages for particular

sections of the manual, which were inserted on some places in the codex.

Codex Wallerstein, like many other medieval and Renaissance Fechtbücher,

contains a wide range of sections devoted to particular weapons and kinds

of fighting: part A comprises sections on long sword (Bloßfechten),

wrestling (Ringen), dagger (Degen), and falchion (Messer),

and consists of images provided with relevant comments. On the other hand,

part B–comprising the long sword Bloßfechten, Harneschfechten

‘armoured combat’ with long swords, long swords together with shields,

lances and daggers, judicial shields and swords, judicial shields and maces,

unarmoured wrestling–consists of images only, without any comments or explanations.

This manual, as many other fighting manuals,[6]

puts considerable stress on judicial duels, which is certified by several

elements typical for such kind of fighting. For example, No. 1 verso and

No. 2 recto,[7]present

a remarkable scene of a duel on a fenced yard, with coffins already prepared

for both combatants; moreover (apart from such obvious elements like judicial

shields and maces), one’s attention is drawn by the crosses on the garments

of combatants in part B.[8]

The distribution of sections devoted to particular kinds of combat in

part A is very uneven: the most prominent place is held by unarmoured wresting

(No.15 recto—No.20 verso, and No.33 recto—No. 74 recto: 94 pages), followed

by unarmoured long sword combat (No.3 recto—No 14 verso, and No.21 recto—No.21

verso: 26 pages), unarmoured dagger combat (No. 22 recto—No.28 verso: 14

pages), and finally, unarmoured falchion combat (No. 29 recto—No. 32 verso:

8 pages). Apart from that, section A contains an image of a man-at-arms

(No. 1 recto), the scene of a judicial duel (No. 1 verso—No.2 recto), a

rather ridiculous piece of advice on how to kill a peasant with a knife

(No.74 verso), and the depiction of four persons in courtly costumes (No.

108 verso).[9]

Although such presentation of the material is not a peculiarity of this

manuscript (another example could be Talhoffer’s Fechtbuch aus dem Jahre

1467, where, for example, comments on long sword unarmoured combat

are divided into two sections),[10]

the fact that sections on particular weapons are mixed with one another

to such extent makes the researcher wonder about the way in which the manuscript

was actually written. It could be tentatively suggested that the scribe

proceeded gradually, writing or copying particular sections as he had access

to relevant data, without caring about putting the material in a coherent

order. Moreover, the scribe of part A was in all probability not very familiar

with the Kunst des Fechtens. To support this point of view, one

can refer to No. 9 verso and No. 10 recto, when the scribe simply confused

the comments to two images with each other—at least, he realized his mistake

and provided the images with relevant explanations. On the other hand,

it could be supposed that the manuscript was first illustrated, and then

provided with comments; however, the fact that the scribe confused the

comments for two entirely different techniques speaks a lot about his knowledge

of the subject.

Of interest is the fact that in the first seven plates of the long sword

section (No. 3 recto—No. 6 recto) there are headings with general fighting

principles:[11]

written just above the first line of the comments, and with a different

script, they are in all probability later additions.

The aim of this contribution is to present brief remarks on the long

sword section of part A of the manuscript: for the audience’s convenience,

the relevant pages will be referred to from now on by single numerals,

without the use of recto—verso division. Thus, the numeration will be as

follows:

-No.

1 recto: plate 1,

-No.

1 verso: plate 2,

-No.

2 recto: plate 3,

-No.

2 verso: plate 4,

-No.

3 recto: plate 5,

-No.

3 verso: plate 6,

-No.

4 recto: plate 7,

-No.

4 verso: plate 8,

-No.

5 recto: plate 9,

-No.

5 verso: plate 10,

-No.

6 recto: plate 11,

-No.

6 verso: plate 12,

-No.

7 recto: plate 13,

-No.

7 verso: plate 14,

-No.

8 recto: plate 15,

-No.

8 verso: plate 16,

-No.

9 recto: plate 17,

-No.

9 verso: plate 18,

-No.

10 recto: plate 19,

-No.

10 verso: plate 20,

-No.

11 recto: plate 21,

-No.

11 verso: plate 22,

-No.

12 recto: plate 23,

-No.

12 verso: plate 24,

-No.

13 recto: plate 25,

-No.

13 verso: plate 26,

-No.

14 recto: plate 27,

-No.

14 verso: plate 28,

-No.

21 recto: plate 41

-No.

21 verso: plate 42.