The Flower of Battle

A Medieval Italian Fencing Manual

Journal of Western Martial Art

June 2003

by Matt Galas

Editor's note: This article was originally published in the Hammerterz Forum, Winter 1995/96, vol.2 no. 3 and has been substantially updated from

what appeared in noted Hammerterz Forum issue. The author has continuously updated his

interpretation of Liberi and has included any improvements made to the

interpretation in the current article. Regardless, the article is still

substantially the same as it appeared in Hammerterz Forum publication indicated. Get your own copy of Hammerterz Forum Collected, a 8x10 inches, and cerlox bound manuscript containing 364 pages covering the issues published between the Summer of 1994 to the Fall of 1999.

uring the 14th and 15th centuries, Italy was a patchwork quilt of warring states. The constant strife between the great cities - Florence, Milan, Venice, Genoa - kept the country in a permanent state of unrest. Their hired armies, led by mercenary captains called Condottiere, laid waste to the countryside. French, German, and Spanish armies, seeking to carve kingdoms from the chaos, made regular incursions into the peninsula. Rival claimants for the Papacy fought battles of their own, while sporadic outbreaks of bubonic plague inflicted further suffering on the already burdened populace.

uring the 14th and 15th centuries, Italy was a patchwork quilt of warring states. The constant strife between the great cities - Florence, Milan, Venice, Genoa - kept the country in a permanent state of unrest. Their hired armies, led by mercenary captains called Condottiere, laid waste to the countryside. French, German, and Spanish armies, seeking to carve kingdoms from the chaos, made regular incursions into the peninsula. Rival claimants for the Papacy fought battles of their own, while sporadic outbreaks of bubonic plague inflicted further suffering on the already burdened populace.

In the midst of these troubles lived a fencing master named Fiore dei Liberi. Born in the northern Italian village of Premariacco, Maestro Fiore is first mentioned in public records dating from 1383. Maestro Liberi studied under a number of masters, and travelled widely. He was clearly influenced by the German long sword school which flourished on the other side of the Alps. In the forward to his work, Maestro Liberi states that he was schooled in both the German and the Italian doctrine of arms. In particular, he gives credit to "Master Johannes, called the Swabian, who was a scholar of Nicholai of Toblem, of the diocese of Metz." Swabia is a region in Germany; Metz is located in Lorraine, France, but was often in German hands. Interestingly enough, one of his guards (Porta di Ferro) is identical in both form and name to a German guard with the long sword, called the Eiserne Pforte (Iron Gate).

By 1410, when he published his treatise on knightly combat, Maestro Fiore was a well-established master with 50 years of experience and a deadly repertoire of techniques. Entitled Flos Duellatorum (The Flower of Battle), his illustrated manual covers the use of all the principal knightly weapons - sword, lance, dagger, and poleaxe. In keeping with the necessities of medieval warfare, Maestro Fiore taught his students to fight both on foot and on horseback. Likewise, his manual covers techniques for both armored and unarmored combat. The bulk of the treatise consists of illustrations followed by short, rhyming captions. Fiore's manual survives in three versions, each with slight differences. It appears that two others existed, but they remain lost to history. This article relies on the version published in facsimile format by Francesco Novati in 1902.

The illustrations begin with a lengthy section on wrestling techniques, many of which are designed to defeat a knife-wielding opponent. Since the dagger was such a common weapon, another section covers dagger techniques designed to counter a swordsman's attacks. The master shows himself to be a consummate wrestler. This is evident in each section of his manual, as he thoroughly integrates wrestling into all of his weapon techniques.

After a few pages devoted to the one-handed sword and the spear, the manual turns to the Spadone (great sword). He begins by illustrating a series of Posta, or guard positions used with the sword. Maestro Fiore assumed a certain amount of skill on the part of his audience; spending little time on the basic cuts and thrusts, his treatise skips to a series of specialized techniques for long range (gioco largo) and close combat (gioco stretto). Most of the close range techniques involve trapping or disarming moves aimed at neutralizing the opponent's sword.

The next group of illustrations deals with armored combat on foot, primarily using the sword. Holding the sword grip in his right hand, the knight grasped the middle of the blade with his left hand, using his Spadone like a short spear. This method allowed the swordsman to aim forceful, accurate thrusts at gaps in his opponent's armor. Another series of techniques covers the use of the poleaxe.

Following this is a chapter on mounted combat with sword and lance. This section is supplemented by illustrations of a dismounted spearman defending himself against a mounted foe. The spearman uses a specialized type of lugged or winged spear known to arms and armor experts as a Friulian spear, after Maestro Fiore's home province.

In most of the illustrations, the victor is designated by a black garter around one of his legs. More often than not, the victorious fighter is an older man with a forked beard, wearing a cloth headband. Since medieval fencing masters commonly posed for their own manuals, this bearded swordsman most likely represents Maestro Fiore himself. A more complete description of this manual appears in an appendix at the end of this article.

The remainder of this article gives a sampling of Maestro Fiore's techniques. The majority illustrated here concern the Spadone, since it is covered more extensively than any other weapon in the manual.

Self Defense Against Knife Attacks

The dagger was an indispensable part of medieval attire. Thus, when fighting broke out, it was the most frequently encountered weapon. Maestro Fiore's manual contains numerous techniques for disarming a knife-wielding assailant.

|

|

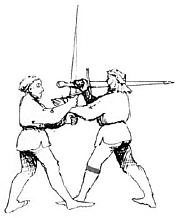

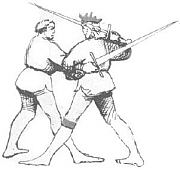

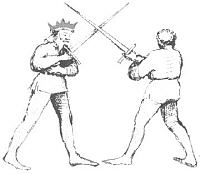

| Figure 1 |

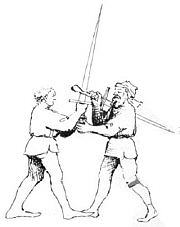

Figure 2 |

- Against a downward, stabbing attack, the man on the left catches his opponent's wrist. Reaching underneath the knife with his right arm, he strikes the knife blade to the right with the back of his hand. This forces the weapon toward the weak point of the knife-man's grip - where his fingertips meet his palm. The attacker's grip is broken, and the dagger falls from his hand.

- After grasping his enemy's wrist, the man on the left catches hold of the flat of the blade, pushing forward at his opponent's face. Again, this takes advantage of the hand's weak point, twisting the dagger from the attacker's grip.

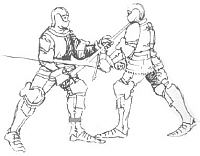

Unequal Weapons - Dagger vs. Sword

Our stereotype of chivalry as fair play is a creation of Victorian romantics - the idea of giving up a battlefield advantage would seem foolhardy to the medieval swordsman. Given the emphasis on disarming techniques, one might easily find himself with only a dagger, facing a foe armed with the Spadone.

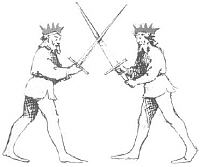

|

|

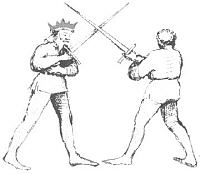

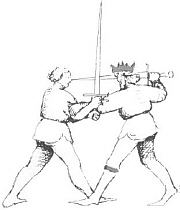

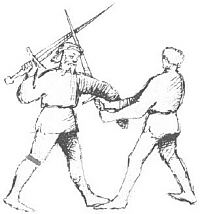

| Figure 3 |

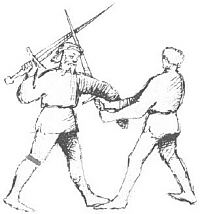

Figure 4 |

- Taking advantage of the longer range of his weapon, the swordsman thrusts at his opponent's belly. Holding his dagger point-down for a stronger grip, the knife-man parries the swordsman's thrust to his right. Quickly closing distance, he steps in with his left foot, catching hold of the swordsman's arm. This prevents the swordsman from escaping to a safer distance. Once in this position of advantage, the knife-man can dispatch his foe with a dagger thrust.

- Against a sword thrust at his face, the knife-man lifts his elbow, striking the point to his left with his dagger blade. Stepping in with his right foot to close distance, he again catches hold of his enemy's sword arm.

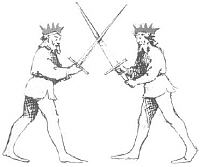

The Spadone (Great Sword)

Maestro Fiore devotes much attention to the Spadone because of its versatility. Although mainly a two-handed weapon, his illustrations make clear that it is light enough to be used with one hand. The master uses it equally to cut and thrust. He also makes frequent use of close-range blows with the pommel, primarily at the face.

Figure 5

- This drawing illustrates the primary cuts with the Spadone - diagonally downward, diagonally upward, horizontal, and vertically downward. Each of these cuts can be made from either side. Surrounding this illustration are allegorical figures of the warrior virtues: Prudence, Celerity, Audacity, and Strength. Prudence holds a mathematician's compass; Celerity, an arrow representing speed; Audacity, a heart; while Strength is an elephant bearing a tower on his back.

|

|

|

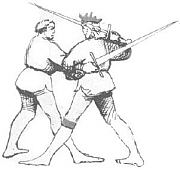

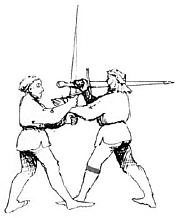

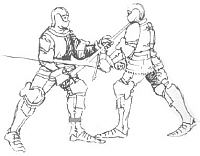

| Figure 6 |

Figure 7 |

Figure 8 |

- After briefly discussing the main cuts, parries, and stances, Maestro Fiore jumps to a series of techniques for close combat. Most of these begin from the engaged position pictured here, formed when a swordsman parries his opponent's downward cut. Both swordsmen stand with their right feet forward, their blades crossed on the inside line. The resulting position is similar to a Quarte engagement in modern fencing.

- From the engaged position in paragraph 6, Maestro Fiore (wearing the black garter) slides his sword down the opposing blade, thrusting with opposition at his opponent's throat.

- The majority of techniques shown in this section involve trapping and immobilizing the opponent's sword. From the engaged position shown earlier, Maestro Fiore steps forward with his left foot. As he does so, he releases his sword grip with his left hand, reaching over the opponent's blade and wrapping his arm around it. Trapping the blade under his armpit, he catches hold of the uppermost quillon; this prevents his opponent from pulling his sword free. With the opposing blade trapped, the swordsman delivers a one-handed thrust at his adversary's belly.

|

|

|

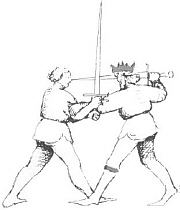

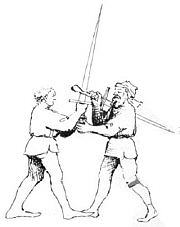

| Figure 9 |

Figure 10 |

Figure 11 |

- From the Quarte engagement, Maestro Fiore steps forward with his left foot; his sword remains engaged to prevent a stop thrust by his opponent. Reaching over his sword with his left hand, the maestro catches the sword grip between his adversary's hands. The follow-up technique is a thrust to his opponent's face; note that the blade is braced against the maestro's extended left arm, preventing a parry of Quarte.

- Many of these trapping techniques are highly dependent on the location of the opponent's arms and blade. This trapping technique is used when the enemy holds his arms low in the Quarte engagement. Stepping in to close distance, Maestro Fiore reaches over his adversary's quillons, trapping both arms under his left armpit. Compare this technique with number 11.

- If the opponent holds his arms high in the Quarte engagement, Maestro Fiore reaches underneath his quillons, catching hold of his right arm behind the elbow. Pulling his enemy's arm to the left, the maestro clears an opening for an overhand thrust to the face. Note the foot position as well; if the maestro chooses, he can pull his opponent towards him, tripping him over his left leg.

|

|

| Figure 12 |

Figure 13 |

- Disarming techniques were highly valued by the medieval swordsman. This figure and the next show two variations of the same disarming method. From the Quarte engagement, Maestro Fiore closes distance by stepping in with his left foot. Releasing the grip with his left hand, he reaches between his opponent's arms. Hooking around the opposing blade with his pommel, the maestro jerks to his right - while striking up and to the left with his free hand. This motion wrenches the sword out of his adversary's right hand, leaving him open for a killing blow.

- This illustration shows the maestro's attention to minute details. Although quite similar to figure 12, this technique requires the swordsman to catch his adversary's pommel with his left hand. As he jerks to the right with his pommel, he pulls upward on the opposing pommel - twisting it out of his opponent's left hand. In both of these techniques, the swordsman can combine the hooking motion of the pommel with a downward drawing cut to his opponent's head.

|

|

| Figure 14 |

Figure 15 |

- Another series of closing techniques are possible from the other main engagement, shown here. It is similar to modern fencing's engagement in Tierce, except that both swordsmen stand with their left feet forward.

- Reaching underneath the crossed blades, Maestro Fiore wraps his left arm around his opponent's arms. With the opposing blade trapped, the maestro can deliver a killing blow from the right at his adversary's head. Alternately, the maestro can complete the wrapping motion with his left arm. By lifting his hand and pressing down with his elbow, he twists the sword out of his opponent's hands.

Armored Combat

In armored combat, the medieval swordsman usually grasped the middle of the blade with his left hand. When attacking, he used the Spadone like a short spear, thrusting at the joints in his enemy's armor. When defending, he used it like a short staff, striking his opponent's thrusts aside with either the point or the pommel.

|

|

|

| Figure 16 |

Figure 17 |

Figure 18 |

- In this stance, the swordsman's arms are pulled well back in preparation for a thrust at his enemy's face. The primary targets in armored combat are the face, the armpits, the palms of the hands, the inside of the elbows, and behind the knees.

- This is a defensive stance. The swordsman can either parry an incoming thrust to the right or left with his pommel, or he can snap his point around, striking the enemy's attack off to his right side.

- Against a swordsman using his Spadone in a more traditional manner, Maestro Fiore (still wearing a black garter) closes in, making a spear-like thrust at his face. Holding his sword in this manner, the maestro has superior leverage - and can wield his sword much more effectively at close range.

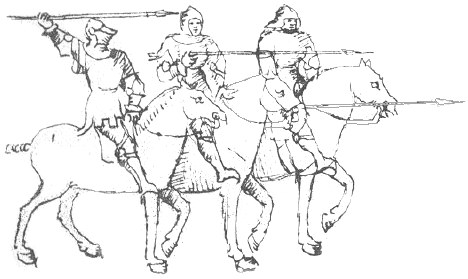

Mounted Combat

The mounted warrior, unlike his comrade on foot, has a very limited opportunity to strike at his opponent. The horses pass one another with such speed that the horseman must deliver his

attacks in swift succession. These attacks usually involve thrusts from the front when approaching the opponent, combined with backwards cuts when passing him by. The primary weapon was the lance, because of its range and penetration.

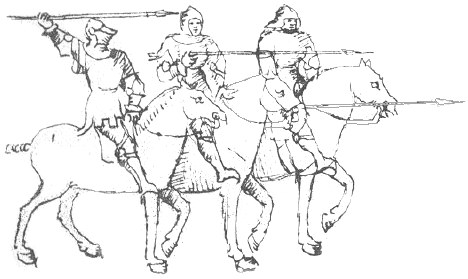

Figure 19

- This illustration shows three methods for using the lance. The first is an overhand thrust, made with a throwing motion. In the second, the horseman holds his lance couched underneath his arm. This method takes full advantage of the weight and momentum of the horse. The third method requires the horseman to hold his lance low, thrusting upwards at his opponent.

Conclusion: The Transition to Rapier Fencing

Maestro Fiore was a typical fencing master of the medieval school - expert in all weapons, and devoted to preparing his students for any situation. In the centuries that followed, armor was gradually abandoned. As a result, both the weapons and the style of combat changed. The Spadone slowly faded away, replaced by the fashionable new rapier. However, it would be a mistake to believe that the thrusting techniques made with the rapier were something radically new and different. Liberi's work clearly illustrates both of the key thrusts so dear to later rapier masters, the Imbroccata (overhand thrust) and Stoccata (underhand thrust), although he doesn't use those terms. The legacy of Maestro Fiore's methods lived on; many of his closing techniques appear in rapier and even later smallsword manuals, adapted for use with these new weapons.

Finis

Appendix:

The following is a more precise listing of the contents of Maestro Liberi's Flos Duellatorum. The number denotes the folio (leaf); the letter denotes the front side (r) and the back side (v).

1r-v: Blank

2r-v: Prologue in Italian and Latin.

3r-v: Blank

4r-5v: 22 illustrations of wrestling techniques, each accompanied by a caption in the form of a rhyming couplets. These rhyming couplets are the standard caption throughout the rest of the work.

6r-12v: 81 captioned illustrations of knife-fighting techniques, including an extensive number of knife disarms.

12v-14v: 18 captioned illustrations of (one-handed) sword techniques. The swordsmen are unarmored. 8 of these illustrations involve thrusts (7 are Imbroccata), while only 2 show cuts. The remainder involve stances, disarms, or trapping techniques. One of the stances shown is intended for throwing the sword at the opponent.

15r: 4 captioned illustrations of mixed weapons wielded by unarmored fighters (dagger and spear vs. spear, two clubs vs. spear, club and dagger vs. spear).

15v-16v: 12 captioned illustrations of spear techniques; the spearmen are unarmored. The spear is held in both hands, except in one illustration, in which it is thrown. This section also shows a stance for throwing the spear or sword. It also shows a stance with the great sword for opposing the spear, as well as unarmed defenses against a spear thrust.

17r-24v 60 captioned illustrations of unarmored techniques using the Spadone (great sword). This weapon is a hand-and-a-half sword, not a two-handed sword. It is shorter than the weapon illustrated in Marozzo's work. It begins with a full-page illustration illustrating the various cuts, as well as the warrior virtues in allegorical animal forms: Prudence, holding a mathematician's compass; Celerity, an arrow representing speed; Audacity, a heart; and Strength, an elephant bearing a tower on his back. Many of the illustrations (18) show stances, including half-sword stances and a position for throwing the sword. Of these techniques, 8 show thrusts being delivered, while 8 show cuts. The remainder illustrate blade engagements, disarms, trapping techniques, pommel strikes, etc. Many of the stances are similar to those used in Kenjutsu (Japanese swordsmanship).

25r-26v: 16 captioned illustrations of armored combat on foot with the Spadone. In nearly all of these techniques, the swordsman holds the sword grip in his right hand, and grasps the middle of the blade with his left hand. Held in the manner, the Spadone is used as a short spear, thrusting at the gaps in the opponent's armor.

27r-28r: 9 captioned illustrations of armored combat on foot with the pole-axe. The variety used is of a type normally called a Bec de Corbin ("Raven's Beak" in French). Maestro Liberi refers to this weapon as the Azza (Axe). The weapon is used with both hands to strike (with either the beak or the hammer head) and to thrust (with either the spike or the butt end).

29r-33v: 32 captioned illustrations of mounted combat between armored horsemen, using sword and lance. Includes disarms and mounted wrestling techniques, the object being to wrestle the opponent from his saddle.

34r: 4 captioned illustrations of combat between footmen and horsemen. The horsemen use the lance, the footman uses the "Friulian spear" (a spear with a cross hilt beneath the point).

34v: This shows a method for stabilizing the lance during a charge on horseback. A cord secures the butt of the lance to the saddle.

35r-36r: 9 captioned illustrations illustrating techniques using the dagger to defend against a swordsman's attack. The swordsmen use both cut and thrust. These include 3 interesting iaido-type techniques for preventing an opponent from drawing his sword. 36r also includes a single illustration of a polearm equipped with a weighted cord for entangling the opponent's legs.

36r: A brief text announces the end of the manuscript.

Hammerterz Forum Collected is available for purchase. It is a 8x10 inches, and cerlox bound manuscript. It is 364 pages covering the Summer of 1994 to the Fall of 1999, the complete print run. Click "here" for more details.

About

the author: S. Matthew Galas, a frequent contributor to Hammerterz Forum, is a lawyer by profession, is one of the pre-eminent modern scholars of the two-handed sword and the fighting arts of medieval Europe.

Journal of Western Martial Art

June 2003

EJMAS Copyright © 2003 All Rights Reserved

uring the 14th and 15th centuries, Italy was a patchwork quilt of warring states. The constant strife between the great cities - Florence, Milan, Venice, Genoa - kept the country in a permanent state of unrest. Their hired armies, led by mercenary captains called Condottiere, laid waste to the countryside. French, German, and Spanish armies, seeking to carve kingdoms from the chaos, made regular incursions into the peninsula. Rival claimants for the Papacy fought battles of their own, while sporadic outbreaks of bubonic plague inflicted further suffering on the already burdened populace.

uring the 14th and 15th centuries, Italy was a patchwork quilt of warring states. The constant strife between the great cities - Florence, Milan, Venice, Genoa - kept the country in a permanent state of unrest. Their hired armies, led by mercenary captains called Condottiere, laid waste to the countryside. French, German, and Spanish armies, seeking to carve kingdoms from the chaos, made regular incursions into the peninsula. Rival claimants for the Papacy fought battles of their own, while sporadic outbreaks of bubonic plague inflicted further suffering on the already burdened populace.